As a Civil Rights activist and former member of the Black Panther party, Howard Fuller’s current passion for education reform may strike the average reader as a strange hobby.

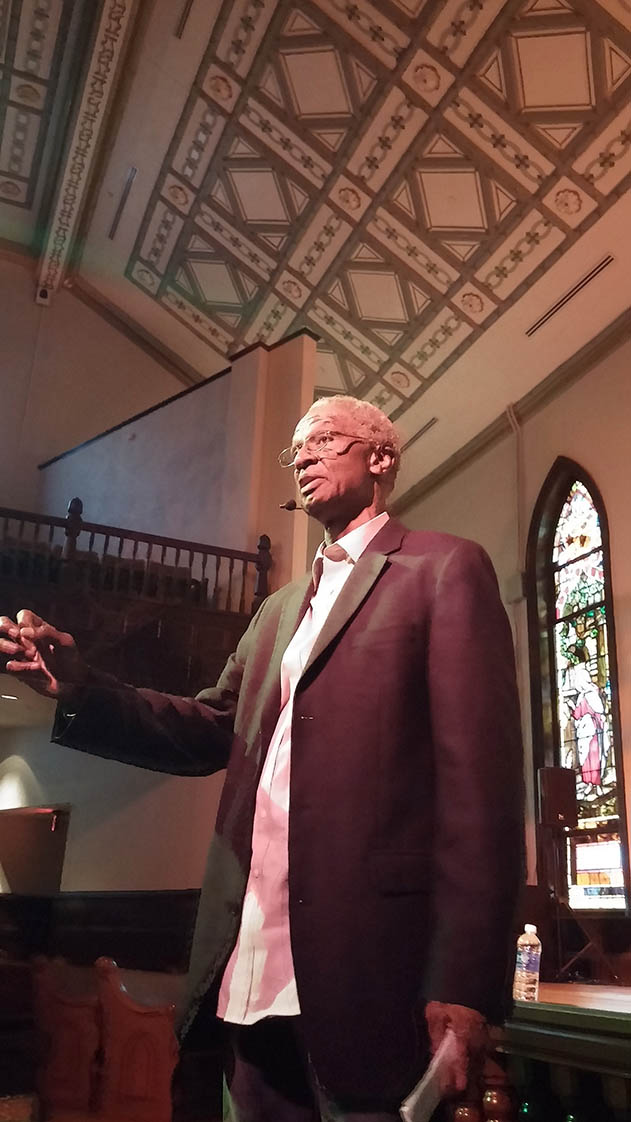

Howard Fuller, former Black Panther and current superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools tells the audience that the struggles between race and education reform are an extension of the same problem. Staff photo by Sarah DeWeese

At Hayti Heritage Center in Durham on Sunday, Oct. 12 Fuller discussed his autobiography No Struggle No Progress: A Warrior’s Life from Black Power to Education Reform. Audience members asked Fuller about the book and his experiences but Fuller always brought the conversation back to fighting racial inequality through education reform.

“I see the struggles with race and education reform as an extension of the same problem,” said Fuller.

Racial inequality led to unequal opportunities in education, according to Fuller. He explained how his fight for equality started with the war on poverty.

Terry Sanford, the governor of North Carolina in 1965, created the North Carolina Fund to fight poverty in Durham. The legislation that went into creating the Economic Opportunity Act was modeled after the North Carolina Fund and started President Johnson’s War on Poverty platform. Operation Breakthrough, a result of War on Poverty, brought Fuller to Durham.

Fuller said, “When I came to Durham in 1965, I came to work for Operation Breakthrough which was a community action program created by the War on Poverty.”

Operation Breakthrough divided Durham into three areas. Fuller was in charge of Area A, which was divided into separate neighborhoods: Hayti, Pickett Street, St. Teresa, Hillside Park, Moorehead, and McDougald Terrace. Later, due to his success, Fuller was placed in charge of the Area B and C as well.

It was through Operation Breakthrough that Fuller enlisted the help of local college students which led to the founding of Malcolm X Liberation University in Durham and Greensboro on Oct. 25, 1969.

Fuller said, “One of the things that we did was hire college students to become organizers. And then place these students in different cities.”

In the summer of 1969 students, from Duke University, gathered and talked about the state of the administration with Fuller. The students reached the consensus that things were moving too slowly in terms of equality on campus. They decided that there was a way to speed the process of equality along: by taking over the Allen building.

Fuller said, “We struggled with the administration to do an Afro American studies program. And the administration was not moving on that.”

The students also wanted more financial help for school and equal opportunities on campus. Fuller was giving a speech at Bennett College in Greensboro, NC when he heard about the takeover.

“I rushed over there and got in… got in through a backdoor or something and this is earlier in the day. And there was a lot of discussion in that building about it,” said Fuller.

He recalled how the students lost their nerve as the day wore on.

“You start hearing students say, ‘my momma didn’t send me here to get arrested.’”

Fuller managed to get the students out of the building before the police arrived and tear gassed the top floor they recently evacuated. The Afro American studies program was not added at Duke University following the event.

“It was then that we came up with the idea of creating an independent college. And we decided to call it Malcolm X Liberation University,” Fuller said.

But even starting their own university was a struggle. Funding did not come easily and the students eventually received the funds through the Episcopal Church in a grant from the General Convention for Special Projects.

GCSP realized the money was for Malcolm X Liberation University after the money was given, resulting in an uproar in North Carolina. Fuller had to go to New York to meet with the presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church.

“I had to explain that we were not going to be involved with training guerrilla fighters and all of that,” said Fuller

“But it was a little… tense in North Carolina at that time.”

The university lasted four years before the funding ran out.

Fuller said his experience with MXLU led him to realize that funding opportunities for minorities were limited and the lack of opportunities fostered racial inequality. He is now a strong advocate for the voucher system allowing low-income students into private schools.

CORRECTION: IN AN EARLIER VERSION OF THIS STORY, WE ERRED IN NAMING FULLER THE CURRENT SUPERINTENDENT OF MILWAUKEE PUBLIC SCHOOLS. See the corrected paragraph below. The VOICE regrets the error.

Fuller, the former Superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools (1991-1995), is a professor at Marquette University and the leader of the Fuller Torch Fellows Program. The program was founded by Fuller as a means of getting input from younger people about problems and solutions for education reform.

One of the fellows, Nikotris Perkins, came to hear Fuller speak in Durham.

“In general, we meet once a month to come up with ways to bridge the gap in equal educational opportunities,” she said.

Perkins and the other Fuller Torch Fellows came to Durham to support Fuller on his book tour. His story, No Struggle No Progress is heavily based on his experiences in Durham and the photo on the cover is from the silent march in Durham the day after Martin Luther King, Jr. died, April 5, 1968.

“He is going to 29 cities in 29 days or something like that,” Perkins said. “But the fellows are only coming with him today because Durham was such a huge part of his story.”

Other supporters were his long-time friends and Durham residents James and Annie Ballentine.

“I’ve known Howard a long time. We were a part of CAP and Operation Breakthrough together back in the ‘60s,” Annie said. She and her husband, James, have been married 56 years now and were a part of many of the events discussed in Fuller’s book.

Near the end of Fuller’s speech he mentioned how his viewpoint has changed from the ’60s, to his current work.

“When I was younger, I really thought I could change the world. Today, I feel like I am on a rescue mission,” he said. “I genuinely hope that young people still want to change the world though because one of them actually might one day.”