Ken Rumble, left, played the role of a white auctioneer as A.yoni Jeffries, right, performed as a black artist at an auction. (Photos by Derrick Beasley, @brobeas)

The dynamic creation “Buy My Soul and Call It Art” engaged the Durham arts community in an essential conversation about the experiences of black artists through a series of performances the weekends of Jan. 26 and Feb. 2.

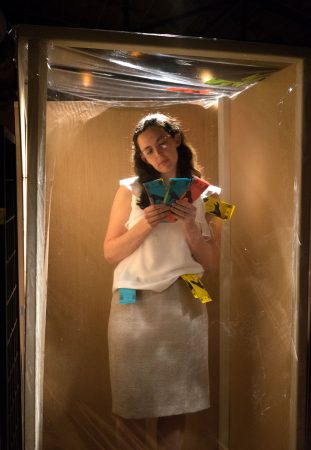

Monét Noelle Marshall is the mastermind behind “Buy My Soul and Call It Art,” an interactive performance exploring the roles of race in the arts industry and beyond. (Staff photo by Marissa O’Neill)

Monét Noelle Marshall, of east Durham, is the creator of this project, which she refers to as a “performance art experience.” Held at the Living Arts Collective in northern Durham, the show featured a cast of 22 self-identified black and non-black artists from the Durham community and was comprised of a series of live exhibits driven by audience participation.

The immersive performance allowed the audience to explore the roles of race, gender, class, money and emotional labor not only in the context of the arts community, but in broader society, Marshall said. The inspiration for the piece is an accumulation of Marshall’s experience as an artist and her work in racial equity.

“I don’t have answers,” Marshall said. “I just have lots and lots of questions.”

The performance flowed as a seamless cycle – each audience was a part of the experience for about 45 minutes with new audiences cycling through the exhibits every 20 to 30 minutes. Upon check-in, each audience member was asked how much black art is worth to them and allotted a stack of play money to reflect the response which would be used to “tip” the artists throughout the performance.

Leroy Ediage dances joyfully in a clear box which separates him from the audience. (Photo by Derrick Beasley, @brobeas)

A guide led the audience to the first exhibit featuring an energetic and optimistic black artist, Leroy Ediage, dancing in a clear box. The audience was encouraged to tip the dancer. Moments later, it became clear that he would never touch the money as the audience was guided to the other side of the box where white philanthropists sorted through the money, complaining about the lack of funds to support their foundations. Ediage, unaware of what was occurring on the other side, began to look around and ask the audience where all of his tips were going. The first scene set the stage for the series of other challenges the audience would soon face as they continued through the live exhibits.

The performance required the audience members to bring their own experiences and to think creatively when processing and responding to the scenes. The audience was challenged to decide between conforming to society’s standards or rejecting the seemingly inescapable situation and responding in a new way.

“I want us to explore and to really interrogate the things that we just decided are the way we do things,” said Marshall. “People are so surprising. Audience members were making choices and doing things I had never even imagined that people would do.”

The cast members ranged from people who Marshall had known or worked with for years to friends of friends she had never met.

“When I put the cast together, I knew I would need black cast members and white cast members,” said Marshall. “And I wanted to be intentional about who I brought together.”

Meg Stein, in the role of a philanthropist, counts the tips from the audience. (Photo by Derrick Beasley, @brobeas)

The third scene was an auction, drawing parallels between the slave market and the arts market. Ken Rumble, 44, a writer and poet from Durham’s Lakewood neighborhood, performed as a white auctioneer. Anna Yoni Jeffries, who goes by the professional name of A.yoni, is a 23-year-old singer-songwriter from Durham’s West End neighborhood, played the role of a black female artist.

Dressed in only a black leotard, Jeffries stood exposed on a podium, a photograph of herself blocking her face. The audience was transformed into auction bidders as Rumble began to yell out starting bids. The audience was then left to ponder if the auction was for the photograph on face value or the artist herself, representing a deeper system at play.

“Part of the brilliance of the piece is that on one level it is sort of simple, but it puts so much pressure on the audience,” said Rumble.

Rumble and Jeffries said that the scene sparked a lot of resistance: in about half of the performances, no bids were placed.

The pair developed a trusting relationship through the development of their scene and the cast quickly became another family, a new community.

“Without even really thinking about it or talking about it, we just became very conscientious stewards of each other’s emotional space,” said Rumble.

Rumble and Jeffries both said that they knew very little about the project going into it. Rumble learned through his wife, a friend of Marshall. Jeffries heard from Marshall directly, who she knows through their involvement together with Black Space, an Afro-futuristic tech hub that caters towards youth.

“The only real way that we can ever reach another person is through the mind.” said Jeffries. “So, for someone to have an experience where we’re not telling you anything — we didn’t say what you should do, what you shouldn’t do, what you can’t participate in; this is the way the world works.”

The intersectionality of money, power, labor and race was a major theme of the work. These themes were explored through a diverse range of exhibits. Black joy was celebrated through dance and Solange’s song F.U.B.U (For Us, By Us). Emotional labor was analyzed through a mock restaurant scene where the audience could purchase items such as “a smile” or “consolation” from the waitstaff.

“For the real issues that we have at hand – money can’t solve those problems – so it makes you think outside the box,” said Jeffries, “like, what can solve that problem?”

At the end of the experience, audience members met with Marshall one by one as she asked the daunting question, “How much will you pay me for my work?” Marshall explained that this was really more of a test for the audience and not a reflection of her art.

“Capitalism tells us that there is a price tag on every single thing, but that is actually a lie,” said Marshall. “There are some things that are priceless. Our souls are priceless. Our art is priceless.”

“Buy My Soul and Call It Art” is the first part of a larger trilogy. The second performance, “Buy My Body and Call it a Ticket,” will run on the weekends of June 8 and June 16, and the final performance, “Buy My Art and Call it Holy,” will run in December.

For a printer-friendly version of this story, click here.