It is estimated over 800,000 people attended the March for Our Lives in Washington on March 24. Many of those attending made signs. On Pennsylvania Avenue, an unidentified man held up a sign that said, "My favorite part of the 2nd Amendment: well-regulated." (Staff photo by Ramishah Maruf)

Exactly 39 days ago, I received a text from my mom while I was studying for a Spanish exam in the library. It only had five words.

“There’s a gun at Douglas.”

I was in the middle of reviewing my flashcards, and at first I didn’t care much about the rumor of a gun at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, which was five minutes away from my house in Coral Springs, Florida. I needed to memorize these irregular verbs, and news like this came up often in South Florida. Just last year, a former student arrived in my high school cafeteria with a loaded gun. The same day, our administrators found a 10-page “Terror Day” manifesto from another student.

Then, my phone went off with another text from former classmates I hadn’t spoken to since high school graduation.

“Misha, you have to check the news.”

At the time, I wish I hadn’t. It was an almost absurd feeling, watching the place I grew up in descend into inconceivable tragedy through social media. How are the hallways I’ve walked through for French horn solos and brain brawl competitions drenched in blood right now? How has the school I spent four years rooting against in football games undergone a tragedy this immense? And how are there 17 people from Parkland and Coral Springs that just…aren’t here anymore?

Everyone was connected to each other in this small community. I’ve competed against some of the victims in band competitions, seen them pop-up on my Twitter feed now and then over the years.

Jennifer Hudson ended the March for Our Lives in Washington on March 24 with a cover of Bob Dylan’s protest anthem “The Times They Are a-Changin.” Hudson has been deeply affected by gun violence. In 2008, she lost her mother Darnell Donerson, brother Jason Hudson and 7-year-old nephew Julian King to gun violence.

So that’s how I found myself, along with 800,000 other people, in Washington last Saturday for The March for Our Lives. I was afraid that my hometown would become another statistic, turning into a depressing household name like “Columbine” and “Sandy Hook.”

But as I marched down Pennsylvania Avenue with thousands of people who had never even heard of Parkland before February 14, I realized I was wrong. The students from Parkland turned around the national conversation and are holding our elected officials and the National Rifle Association responsible for their complacency and lack of action.

I am proud of my community for turning unimaginable grief into a push for real change. Yet a large part of me feels guilty that we have captured the country’s undivided attention, because I am aware of our privilege. Parkland and Coral Springs are two wealthy areas of Broward County, characterized by gated communities and Lexus sedans as sweet 16 presents. And Douglas, which my more disadvantaged high school often ridiculed as being the “rich kid school,” is almost 60 percent white.

While teenagers protesting police brutality in Ferguson were met with racially-charged criticism and tear gas, the teenagers in Parkland received positive media attention and large donations. And as this mass shooting came as a cold shock to my quiet suburb, gun violence is an omnipresent plague in urban communities such as Durham.

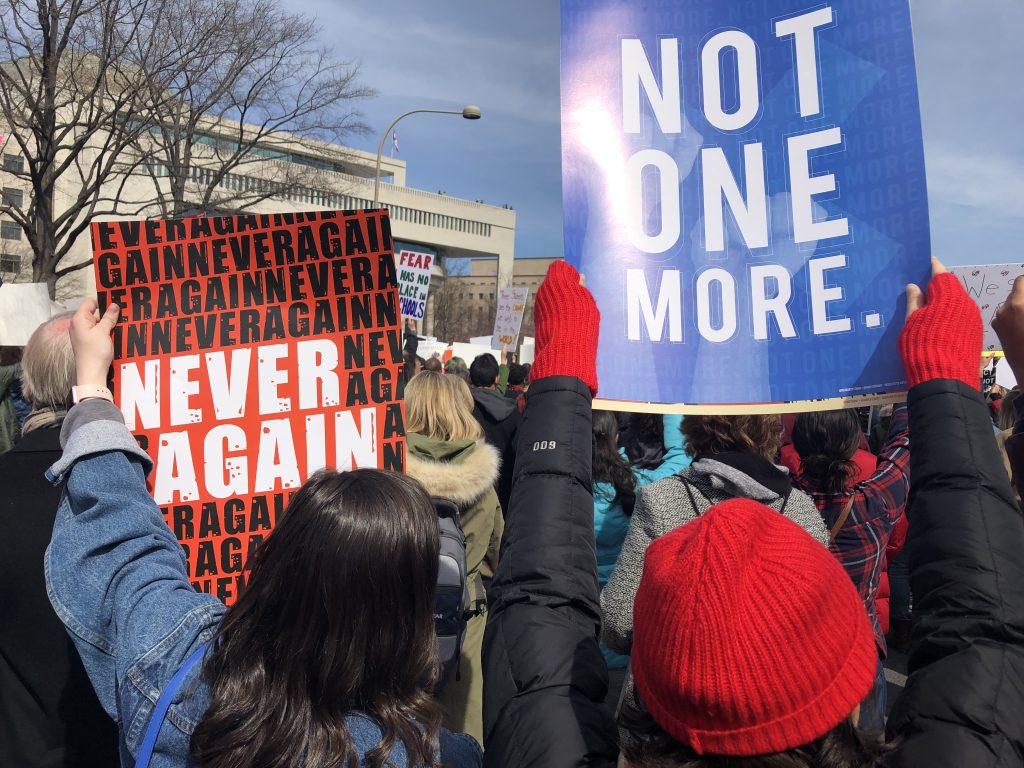

McKenna Urbanski (left) 18 of Concord, North Carolina, and Shadi Bakhtiyari (right), 18 of Charlotte, North Carolina, raise their posters in solidarity at the March for Our Lives in Washington on March 24. “It was one of the most powerful experiences of my life,” Urbanski said.

The Durham-Herald Sun reported that 233 people were shot in Durham in 2017. I thought about how 34 people were shot and how it altered the state of my community forever – how is the country silent when 199 more are victims of gun violence?

We’ve cast African-American, Hispanic and low-income victims of gun violence into statistics. It’s dangerous, because we don’t see them as people with colorful stories, but just as another number. And when we only see people as numbers, we don’t want to take action.

Then, I listened to Naomi Wadler speak. She’s only 11, but she organized a walk-out at her Alexandria, Virginia, elementary school last week.

“I represent the African-American women who are victims of gun violence, who are simply statistics instead of vibrant, beautiful girls full of potential,” Wadler said.

I’m ashamed that it took 17 people from my community to die for me to realize this. This horrific violence takes away people with loved ones and compelling stories everyday, but I was just too privileged to notice.

On Saturday, I marched for Gina Montalto and Alex Schachter, who just won a marching band state championship in November. I marched for Nicholas Dworet, who would’ve been swimming at the University of Indianapolis next year. I marched for Cara Loughran, whose 14-year-old smile reminded me so much of my little brother’s, who is the same age and was in school during the shooting just a mile down the road. I marched for Alyssa Alhadeff, Scott Beigel, Martin Duque, Aaron Feis, Jaime Guttenberg, Luke Hoyer, Christopher Hixon, Joaquin Oliver, Alaina Petty, Meadow Pollack, Helena Ramsey, Carmen Schentrup and Peter Wang.

But I also marched for victims of gun violence from marginalized communities, whose stories and passions we do not get to see on the news everyday.

For a printer-friendly version of this story, click here.