April 23, 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

Yes, local small businesses can promote themselves by submitting a blog or opinion piece to be featured on our website. We encourage businesses to share their stories, services, and community impact. To get started, write your piece and send it to us for review at cakenney@email.unc.edu. Once approved, we’ll publish it on The Durham Voice, allowing your business to reach our local audience and build stronger community connections. Stay tuned, as we will also be introducing more formal advertising options in the future!

Great question! We don’t currently offer advertising features on the website, but we plan to introduce this option in the future. Stay tuned for updates as we develop new opportunities!

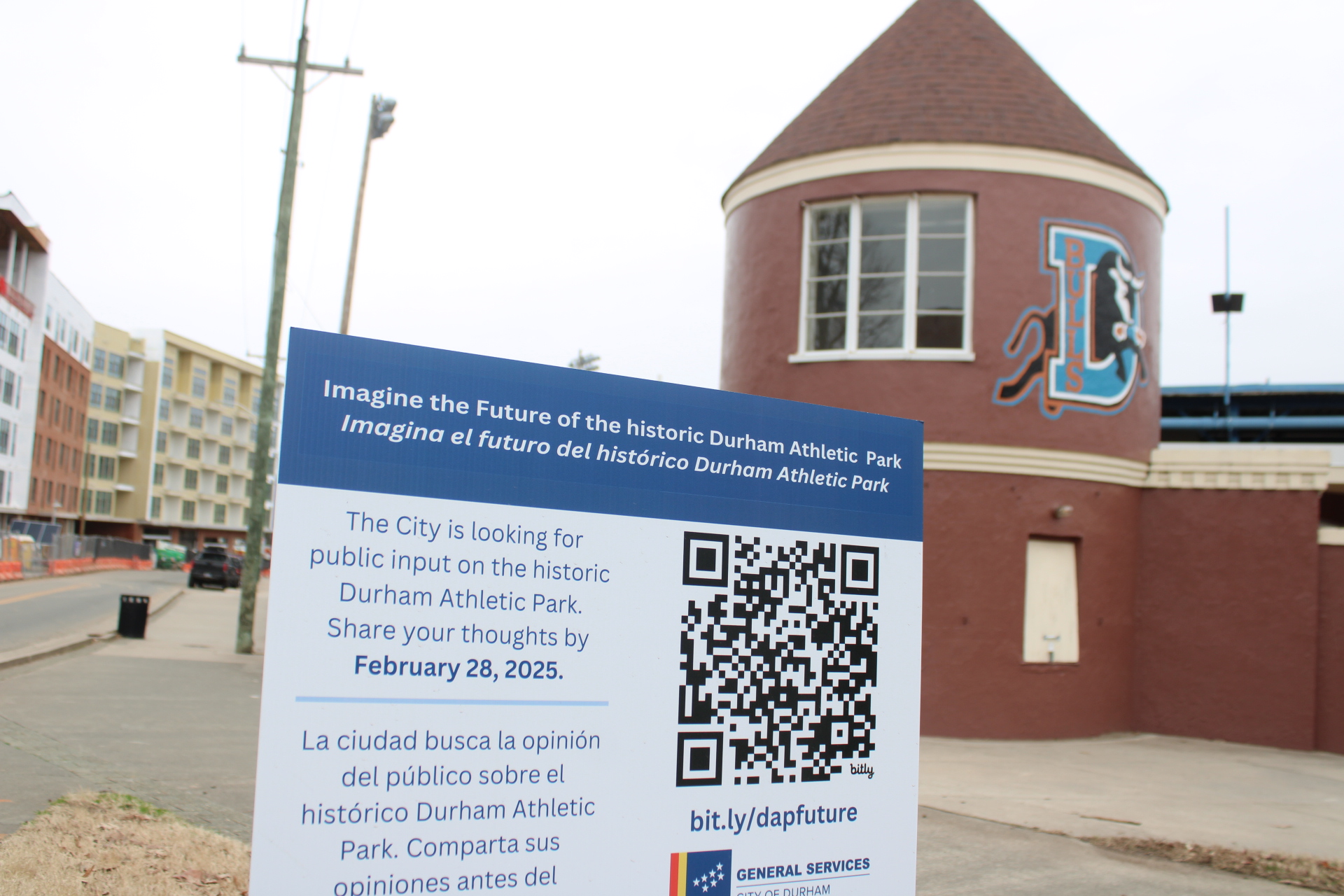

The Durham Voice is an informational website focused on events, stories, and news in Durham County, NC. It highlights local events, issues, and successes, especially for communities often overlooked by larger media. The platform preserves local culture and history by documenting stories and traditions while empowering residents to share experiences and concerns. It also supports local businesses, fostering community connection and engagement. Now, we have many student writers from UNC-CH contributing to the stories. The Durham Voice will serve as a vital source of information for both residents and those outside the city.

We currently don’t have a subscription function due to the rebranding and site updates. But it is a feature that will be introduced soon.

We have a team of student writers from the Hussman School of Media and Journalism at UNC-CH, all professional creators. Stories will be released in rounds, approximately 20 stories per round, every two months.

We welcome new ideas, stories, suggestions, and tips. If you have something interesting to share, feel free to contact Carl Kenney at cakenney@email.unc.edu

To nominate a community leader, you can either send us their name along with a brief description of their contributions and why they should be featured, or you can take the initiative to interview them and write a credible, professional piece for publication. Once complete, submit your story for review at cakenney@email.unc.edu, and we’ll consider it for our next release!