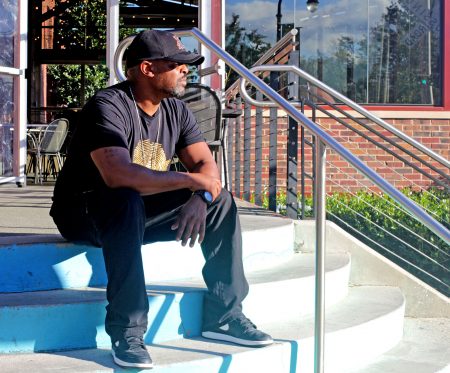

“Red” looks out at the infamous woods of Few Gardens from his townhome. Photo by Autavius Smith.

Growing up as a teen in Few Gardens during the ’70s, you were not getting out of any organized street fights.

If Louis, leader of the “Few Crew,” decided to test your loyalty, anything went.

Jeffrey Harris awaits his sausage pizza at Mellow Mushroom during his lunch break. (Staff photo by Autavius Smith)

Aunts, mothers, cousins and brothers would take the weapons away and circle around the folks duking it out in the neighborhood.

Raised on Morning Glory Avenue in arguably the most violent housing project in Durham, fighting didn’t doom 10th grade dropout Jeffrey Harris to a life in and out of prison.

Like many families in Few Gardens, it was no secret that Harris’ family was underprivileged, making it especially tough to survive. He has spent some time in and out of jail, but he’s a free man, making his way now.

The backdoor to his house was six-feet away from the neighborhood dumpster. Whenever the garbage man didn’t come for pick up, maggots would crawl all over thrown away mattresses and other homeware items.

Now at 46 years old, Jeffrey Harris sat outside Mellow Mushroom restaurant recently, picking sausage from his pizza before talking about his childhood in the projects.

“My first crime ever, my momma gave me a lighter and told me to set the dumpster on fire before we got sick,” Harris said.

He didn’t know when he moved close to the dumpster that he’d contract, bacteria causing him to have stomach ulcers at age 14.

Harris threw up blood for three days.

Margret, his mom, thought nothing of it at first, but after Harris threw up on her gown, he was taken to the hospital.

Doctors claimed if he went one day longer without treatment he would have bled from the inside and died.

That was the ghetto for you, no concern for the health of mothers or children.

The Federal Housing Act of 1949 created three federally funded programs allowing Few Gardens to be Durham’s first public housing project in 1952-53. The 240-unit low-rent housing project located in East Durham was named in honor of the late Dr. W.P. Few, former president of Duke University.

The first wave of gang presence in Durham has been traced back to Few Gardens by North Carolina Gang Investigators Association.

“I wouldn’t have made it if I didn’t find violence usable because I was tried at every point,” said Harris. “It wasn’t Bloods or Crips it was just a serious neighborhood that wanted to see what was in you. I never agreed with it, I was in the band in middle school. I was the only one coming home with a saxophone. Then when I got to high school I got in ROTC.”

Currently, Harris manages the African American News journal, a collection of historic newspaper columns dating back to 1861. He is also the producer of The Peoples Channel, a call-in radio show he hosts using information from books he’s avidly read.

He credited his friends from ages two, three, five and six as his mentors in getting through day-to-day hassles.

“Jat was one of the ones that watch me grow up, he was OG, he made sure that nobody would touch us, nobody would bother us – Nobody bothered nobody because if you did you had to deal with his one-hundred-sixty-pound brother, about 5’9″ with the reputation of a 7’7″ four-hundred-pound boogie man,” Harris said.

Harris’ best friend, “Red,” had an aunt named Paulette who’d often psychically set the record straight with children — even grown men — who were misbehaving in the community.

“The hardest-hitting person out there was Red Bone’s aunt. She had to be from warrior-princess DNA. She was 6’1″, wore Daisey dukes, built like Jackie Joyner-Kersee, gap in her teeth, never did her hair and if you talked to her customer she would let y’all fight,” Harris said.

Red and another mutual friend, Mookie, were put in charge of Few Crew’s secondary gang. Red banned drug and alcohol use after seeing the demise of Louis and several of his friends from drug and alcohol abuse.

“We did a lot of fighting back then, fighting was just the thing, people would lose fights and say, ‘Oh I was drunk.’ No, you just got your ass beat,” Red explained.

Harris calls Red his “blood brother;” the two even acquired their first job doing paper routes as 8-years-olds while gambling for a nickel on the sidewalk.

“I went to school to eat. I had two lunch periods, we were starving in America, in the ’80s, in the projects, that’s when they (government) used to bring us blocks of cheese,” Harris said.

Harris would con one of his friends who’d tear the edges off slices of bread at the lunch table in school.

“It took me years to realize Few Gardens was a fortress. Yeah, we had our crime issues, but that was because of people coming in there buying drugs, if nobody bought drugs they wouldn’t have sold none of it,” Harris said.

According to Harris, in the ’80s a state trooper was beat and had his gun stolen after a visit to Few Gardens to make an arrest went wrong. He says that for years the Durham Police Department was hesitant to respond to reports linked to Few Gardens. Both Red and Harris mentioned at one point there was a substation to secure the neighborhood, but it eventually was shot up when no cop patrolled the station.

In 2003 with a long history of brutal beatings, hour-long fights and drug infestation, Few Gardens was demolished by the city.

“It broke my heart, it killed me because everything we touched was destroyed, where I lived, my schools, everything that showed that I existed (the city government) got rid of it,” Harris said.

Justin Wrath says:

That place was trash and the Few Family was ashamed to have their name on it. Write a story on McDougald Terrace next and how you can buy drugs, guns and humans there.

DumpsterCo says:

That’s the real right there. Many people would struggle to understand the complexity of such a situation. But it’s not so hard considering the stories folks there have to tell.