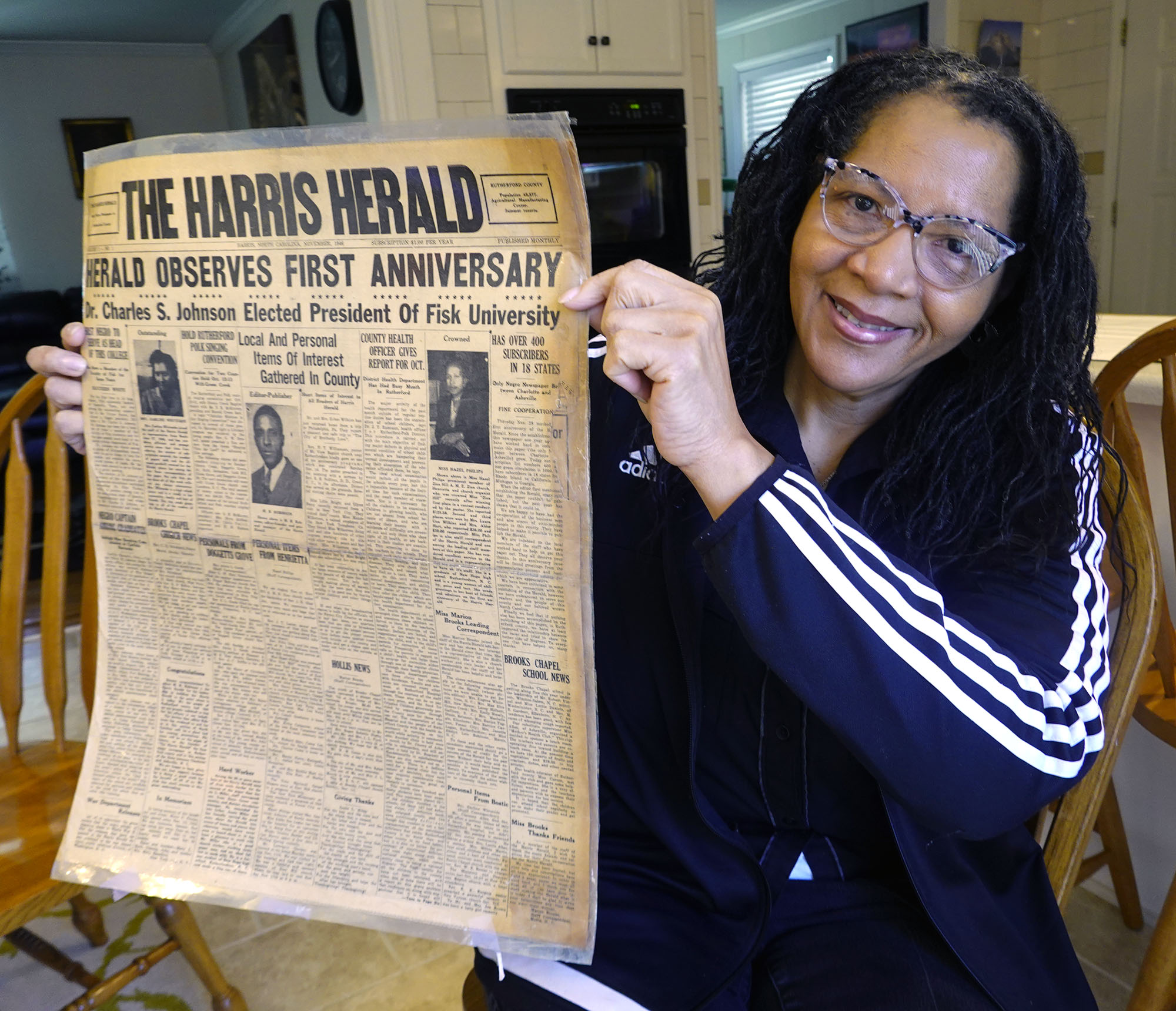

Holding a copy of Milton B. Robinson’s 1946 edition of The Harris Herald, daughter Phyllis R. Washburn of Forest City, says, “There was such an absence of the Black voice at the time. Without this paper there was no voice at all!” (Photo by Jock Lauterer)

Some claim that it’s always Black History Month — so then it’s never too late to celebrate the pioneering work of a bold and enterprising young Black journalist, Milton B. Robinson who, in 1945 launched The Harris Herald, billed proudly as the “Only Negro Newspaper in Rutherford County.”

Robinson’s publication was a groundbreaking, heroic as well as a risky undertaking for a Black journalist working in the post-WWII era in the Jim Crow South.

Based in the tiny crossroads community of Harris in the extreme southern corner of Western North Carolina’s Rutherford County not far from the S.C. state line, Robinson’s monthly filled a void. The old Forest City Courier, like most white-owned newspapers of that era, largely ignored the daily comings and goings of the Black community — births, deaths, anniversaries, weddings, graduations — but was only too happy to take Robinson’s money to print his paper. Or to publish crime stories involving Blacks.

Why I Care

Forgive an old newsie for taking a personal aside here, but permit me to share the back-story to provide context. I spent 11 happy years in Rutherford County, 1969-1980, as one of the co-founders/editors of THIS WEEK and then The Daily Courier.

In my tenure there, I did hundreds of story/photo packages on local blacksmiths, gold miners, molasses makers, dulcimer pluckers, farmers, old-time string band music makers, quilters, actors, cloggers, wood stove cookers, the list goes on — from one end of the county to the other.

And here’s the shameful thing: I consider myself something of a local historian, yet never once did I ever hear of The Harris Herald. More embarrassing, I even lived in Harris briefly one summer and never knew of the paper’s existence.

Fast forward 42 years: I am a retired journalism professor at UNC-Chapel Hill making a research visit last fall to the university’s historic Wilson Library, home of the North Carolina Collection and its Gallery which often features curated educational exhibits.

(The Wilson Library is much beloved to this scribbler, as my grandfather, Charles E. Rush, served as head librarian, 1941-54. Additionally, my grandmother staffed the Rare Book Room during WW II and my mother worked at the circulation desk. So, the Wilson Library is like a second home to me.)

Passing one exhibit case titled, “Papers for the People: A Treasury of North Carolina News Sources, 1880 to the present,” I glanced at the introduction, which read in part, “As in the past, residents of The Old North State turn to serialized publications to get news… of neighbors…Some cater to African Americans…who find little about their communities in the major dailies.”

Then, almost magnetically, my eye was drawn to another exhibit case across the room where a newspaper’s name caught my eye.

THE HARRIS HERALD, the banner nameplate proclaimed in bold all-caps type.

No, I’m thinking. That couldn’t be our Harris. Not my Harris.

But of course, it was. Giddy with an old reporter’s joy at finding a fresh story, I’m sure I made a complete fool of myself when I unloaded on the gallery’s keeper, who listened indulgently as I prattled on about my connection with Harris and Rutherford County.

Bless her heart, for good kind librarian Linda Jacobson told me how three daughters of the Herald’s founder had donated copies of the paper to the library’s archives, and that Bob Anthony, award-winning and newly retired curator of the North Carolina Collection at the Wilson Special Collections Library, had that contact information.

Indeed, Anthony put me in touch with Phyllis Robinson Washburn of Forest City, who, along with sisters Evelyn and Annie, donated 18 editions of The Harris Herald to the University’s North Carolina Collection archives, where the papers will be safely stored, digitized for perpetuity and accessible to qualified media historians and researchers.

Which brings us up to the present. This week, I had the blessing and honor of getting to sit down with Phyllis Washburn at her home south of Forest City and listen to the story of the amazing Milton B. Robinson and his paper, The Harris Herald. Phyllis, 68, a retired high school biology teacher, called on the memories of two older sisters, Annie Jones, 81, of Shelby, a retired special education teacher; and Evelyn Mercer, 87, of Charlotte, a retired math teacher. The interview turned into sort of a four-way phone conversation.

Of the newspapers donated to UNC, Phyllis says, “We didn’t want them just to be sitting around in the closet. They were so important — and this is something special! And, it’s his legacy.”

Milton B. Robinson’s life story reads like the stuff of folk fable. Having survived a difficult childhood when he was shuttled from home to home, young Robinson, at only 16, struck out on his own, riding the rails as a hobo — determined “to overcome his obstacles,” Phyllis recounts, and to make something of his life.

A Meteoric Career Trajectory

“Daddy wasn’t one to sit around,” Phyllis adds, “He used his head,” she vowed, ticking off the palette of job skills her father picked up along the way: “He was very entrepreneurial. He hustled. He bagged peanuts.”

And that’s just for starters. In his busy and productive life, Robinson qualified in many occupations. He shined shoes, was a builder/carpenter, brick mason, farmer, mill worker, real estate agent, preacher, high school teacher, and editor of an AME Zion newspaper.

(He was also a Pullman porter — but I’m asking you to hold that thought for two paragraphs.)

When Robinson settled down Harris in 1939, he built a house for himself and wife Lois and their growing family. Then, he went back to school, even while working at Stonecutter Mill, graduating in 1944 at the age of 31 from old Grahamtown High School in Forest City, where he also drove the school bus to help ends meet.

The theme of education runs through the Robinson family like a mighty river. Of the 11 children born to Milton and Lois Robinson, nine would go on to earn college degrees, including the three sisters who donated their father’s papers to the UNC Library.

The Pullman Porter Influence

After high school graduation, Robinson landed a transformational job as a prestigious railroad Pullman porter.

This latter elite job was among the very top rungs of occupations for a Black man in that segregated era, Phyllis notes. Riding the big trains up and down the main lines during the late ‘40s, the Pullman porters were instrumental in aiding in the Great Migration of Southern Blacks to the industrial Northern cities, according to the PBS documentary, “The Black Press, Soldiers Without Swords.”

The documentary details how, as the train passed through towns and cities up and down the entire North-South route, porters clandestinely would toss out bundles of the influential activist Northern Black newspapers like The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier, thus encouraging disadvantaged Blacks to move north in search of a better life.

There is little doubt in my mind that it was this experience as a Pullman porter that inspired Robinson to return home to Harris and launch the Herald in November 1945 with the expressed mission of raising the living standards and expectations of his readers, as well as helping them better navigate a challenging life in the segregated South.

Daughter Phyllisstill remembers vividly the “White Only” public drinking fountain in the center square of Forest City.

Growing the Harris Herald

Ever resourceful, Robison built a newspaper office out of a train wreck. Literally.

Evelyn tells how a railroad accident in Harris yielded up free salvage materials for locals with a will and a way. “Daddy had a mule and a wagon,” Evelyn explains, and the wrecked boxcar provided high quality lumber for the paper’s first office outside their home.

The sisters each have their own special memories of those days. Phyllis says she can still hear the sound of his manual typewriter, “Peck, peck, pecking…” away.

Evelyn adds that she remembers as a 13-year-old selling The Harris Herald for a dime on Main Street, Forest City.

The 33-year-old editor-publisher never missed an opportunity to promote The Herald, leading the front page in the second edition of the paper, February 1946, with an all-caps, boldface headline, “THE HARRIS HERALD IS WELL RECEIVED” with smaller headlines reading, “Reception Was Greater Than We Anticipated,” followed by, “Scores of People Over State and Nation Expressed Felicitations” and finally, “Sub(scription) List Growing.”

Indeed, a year later, Robinson announces with justifiable pride in his first anniversary celebratory edition, “Only Negro Newspaper Between Charlotte and Asheville — Has Over 400 Subscribers in 18 States” with a pressrun of 1,000 copies.

Robinson’s Herald featured stories and photographs celebrating Black life in Rutherford County: Black service men and women, Black guest speakers and choir events at local Black churches, the crowning of a local Black beauty queen, as well as birth notices, obituaries, anniversaries, and weddings that would likely never appear anywhere else in print.

Phyllis says emphatically, “There was such an absence of the Black voice at the time. Without this paper there was no voice at all! This paper was very important to the Black community.” Phyllis adds, “This is the reason the Black church became so important. It became the only platform to address any issue, political or otherwise. And is still relevant for this purpose today.”

Additionally, Robinson didn’t shy away from taking on tough topics, such as voter access, an anti-lynching bill working its way through Congress, and lack of Black peoples’ access to quality health care in Rutherford County.

But according to Phyllis, when it came to sensitive stories, her father cleverly used “sort of a code, that his readers would understand.” His people could read between the lines. So, in order not to antagonize white advertisers, Phyllis explains, “He had to be very careful about how he wrote; he might have been shut down for what he wrote.”

In that first anniversary edition in 1946, Editor Robinson talks to his readers, both Black and white: “We have been criticized in some quarters for the publishing of the Herald, however we have endeavored to serve our readers… Finally, we feel that if nothing else has been accomplished…we have at least improved the relationship between the races and tried to show the better side of Negroes.”

Although Robinson’s Harris Herald lasted only three years, that’s 36 separate editions, leaving little doubt that this pioneering Black community newspaper had a strategic and positive impact on the lives of many of its Black readers.

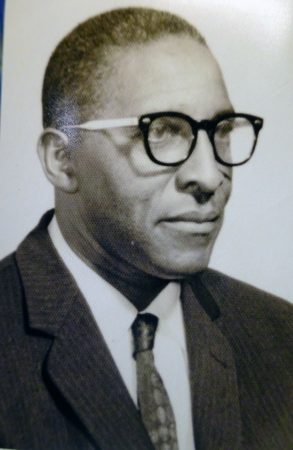

When Robinson ceased publication in 1949, he did it for the best of reasons — when it became evident to him that he needed more than just a high school education. The decision led him to enroll at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte where he earned his bachelor’s degree, followed by a master’s degree from N.C. A&T in Greensboro, and ultimately a doctorate in divinity from Livingstone College in Salisbury. To cap it off, in 1973 Livingstone awarded Robinson with an honorary doctorate — the academic equivalent of a lifetime achievement award.

A Life of Service

By the time Robinson died in 1991 at the age of 78, he had become a highly respected and revered local, state and national leader in church, government and educational affairs. Just a partial listing of Robinson’s many accomplishments and titles: Pastor of churches in both N.C. and S.C., chairman of the Rutherford County Human Relations Council, second vice president of the Rutherford County Democratic Executive Committee, president of the Rutherford County NAACP, member of the board of trustees of Isothermal Community College, Winston-Salem State University and Doggett Grove A.M. E. Zion Church.

To further his legacy, the three Robinson sisters successfully lobbied for the State Department of Transportation to name a bridge over Floyd’s Creek on highway 221 in their father’s honor. The Reverend Milton B. Robinson Sr. Bridge is located south of Forest City close to the house Robinson built himself.

It strikes me that naming a bridge after Robison is a fitting way to honor the work of this courageous Black journalist – for what else is a community newspaper if it is not a bridge-builder?

Speaking for her sisters as well as for herself, Phyllis concludes, “We think he did a great job in his life, coming from where he came from.”

Not too shabby for a run-away hobo.