A exhibit viewer examines the photo of Joslin Simms at the Justin Cook photo exhibit the Golden Belt campus. (Staff photo by Jock Lauterer)

For Joslin Simms, the pain that gun violence has brought in Durham will never end.

“Every time I hear a siren, I relive my son’s murder,” she said. “I think about my son every day, I’m sure like these other mothers do.”

Bonnie Turner, visiting the photo exhibit in which she is featured, above, says that the mothers’ support group has been vital to the community. (Staff photo by Jock Lauterer)

Simms’ son, Ray, was killed in a shooting in 2005. The unsolved murder has left his mother, children and the rest of his family to deal with their trauma with no answers.

Joslin suffers from post-traumatic stress. Ten years later, one of her granddaughters still has dreams about losing her father.

Ray’s youngest child was too young to have a recollection of him. She relies on her family for stories about what her father was like.

“Right now, she knows his favorite thing was sunflower seeds, he loved sunflower seeds,” Joslin said. “She made it a habit of having her mother buy sunflower seeds, and she’d go put them on his grave.”

Parents of murdered sons also have to deal with another burden, as Joslin explained, “A lot of the times, some of these victims are staying in the morgues for weeks at a time because no one can afford to bury them. And that’s another thing that some of us mothers have to go through. And that’s hard, when your child is in that freezer and you’re in limbo because you’re trying to get the money, raise

enough of the money that the funeral home will take to let you make the payment. They want a certain amount straight out, or they won’t touch them. So we’ve got to deal with that, too. It’s like you’re being punished for your child being murdered.

The aftermath of gun violence hasn’t limited itself to one aspect of Joslin’s life. She said she had a friend whose son was recently killed. She knew another victim’s mother who died from health complications believed to be exacerbated by her son’s murder. Simms said she had already heard of four murders in the week she was interviewed.

“You may not know them now, but eventually you’re gonna know somebody that was murdered,” she said. “Try to get the church involved. Get the community together. We need people to stand up, and we need everybody to do their part.”

And that’s exactly what she, with the help of some friends, has been doing.

For about five years, Simms has been attending the Circle of Hope and Healing through the Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham.

She said the circle offers her a way to spend her time, but more importantly, it’s the only place she’s found where she can be herself and address her anger and pain.

“I won’t cry around the kids because they’re still dealing with it in their own way, they’ve victims of their own,” she said. “(At the circle) I can talk openly without nobody saying I shouldn’t say that, I shouldn’t feel this.”

Simms was one of many victims of gun violence that photographer Justin Cook got to know for his ongoing project, “Made in Durham,” which explores the effects of homicide, incarceration and urban renewal in the city.

Marcia Owen is the director for the Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham. She said Cook has been instrumental in helping a community marred by gun violence.

It’s amazing what Justin Cook has done,” she said. “Because there really are two Durhams, and the Durham he wants to bear witness to is the Durham that’s experiencing a homicide every other week, is living at about $18,000 a year, and has just enormous challenges.”

Though Cook has been photographing in the city since he graduated UNC-Chapel Hill in 2005, the latest installment of Made in Durham sprang up Nov. 3. Large prints of some of Cook’s photos, including one of Simms, stand glued to a concrete wall outside the Golden Belt in Durham.

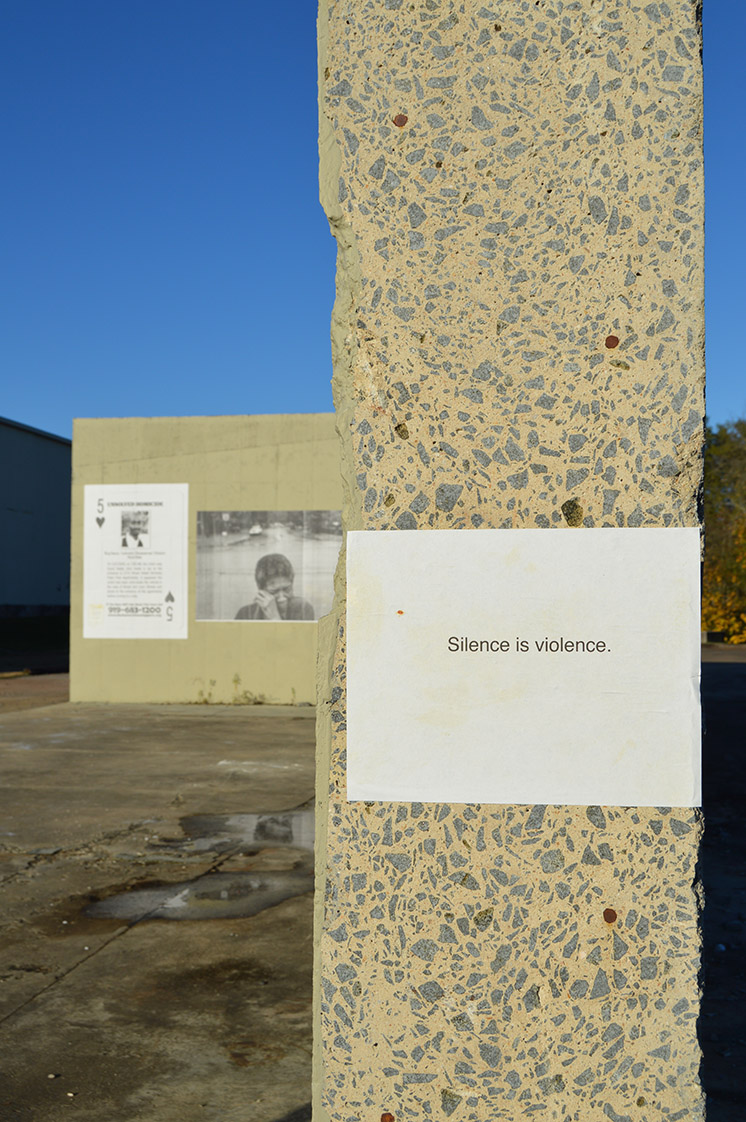

“Silence is violence,” reads one of the markers at the Justin Cook photo exhibit. (Staff photo by Danny Nett)

“We wanted to create basically a space, an event, where people from the pictures, from the community, could come and grieve and celebrate and have more of a platform for their voices,” Cook said.

Two days after creating the display, Cook and other organizers held a vigil at the wall to honor those who have been lost to gun violence. He said a group of about 60 people from diverse backgrounds attended.

For Simms, the vigil offered a chance to grieve, but also an important way for members of the community to see the impact of gun violence firsthand, beyond statistics and news stories.

“I thought it was so beautiful, because, like I said, it represented not just me, but the rest of us mothers who had lost a child,” Simms said. “But when you actually see a picture, especially a picture that large, it touches people more than me just saying, ‘Hey, yeah, I’m a victim of a murdered child.’ It shows more of the story than what I could tell them face to face.”

Simms said solutions might be possible if the community gets together to help end the violence that puts everyone at risk.

“It doesn’t matter anymore where you live, what color you are, ’cause the bullets do not have a name, or a race, or religion,” she said. “We should be able to sit on our porch and talk like we used to. Nobody should have to live like this.”