Blair LM Kelley, author of Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class, shared insights on incorporating her ancestral line into her book’s writing process during the Writer’s Discussion Series Lecture last Thursday evening, November 2.

Kelley is a Ph.D. holder in History with certificates in African and African American studies and women’s studies from Duke University. She also serves as the Joel R. Williamson distinguished professor of southern studies, director of the Center for the Study of the American South, and co-director of Southern Futures at UNC.

The Series is an ongoing program at the Sonja Haynes Stone Center, co-sponsored by the Center for the Study of the American South, the Department of American Studies, and the Bull’s Head Bookshop in the Student Stores at UNC.

With the Series aligning with the Stone Center’s mission of advancing debate on American diaspora issues, Sheriff Drammeh, the Stone Center’s senior program manager, said that Black Folk fell into that topic.

“Writing the way she weaves her personal family background and narratives with history, it’s refreshing,” he said.

Unlike the program’s other events where authors give traditional lectures, Kelley and the Stone Center’s staff opted for a Q&A conversational format they found “more engaging.”

Additionally, the Stone Center’s director and moderator of the event, LeRhonda Manigault-Bryant, used a “call-and-response” tactic, a tradition she said she comes from, to encourage the audience to speak up if something said, “resonated with them.”

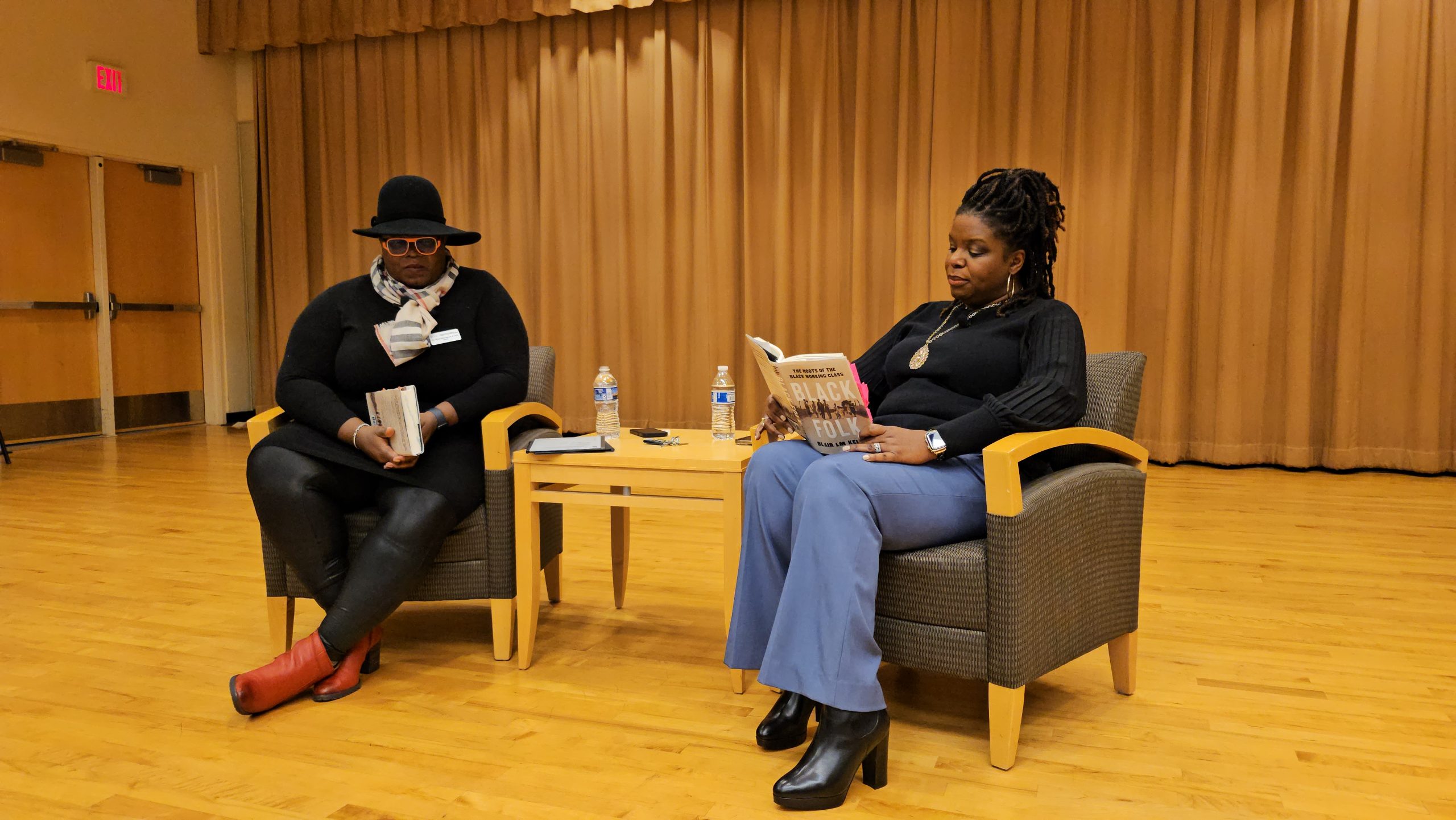

Kelley answered questions about her process of creating Black Folk posed from Manigault-Bryant.

“Dr. Kelley spends a lot of time in that book, talking about connections between her ancestors,” said Manigault-Bryant in an interview a few days before the event. “So I’m really curious in terms of that writing process, how that made its way into the text.”

At the event, Manigault-Bryant said that Black Folk has a narrative that is “character-driven” and “reads like a novel.” She said that as a historian in her career, Kelley has a way of “talking to the dead” that intersects with the way she crafted Black Folk, one of the themes that Manigault-Bryant focused on during the event.

“[With Black Folk being] character driven, it’s actually an archival database. There’s a space that I think of as this kind of rooted imaginings… because it’s speculative. It’s inferred,” she said.

Black Folk, published in June, unfolds history from Kelley’s earliest known ancestor, Solicitor, an enslaved blacksmith to other members of Kelley’s ancestral line and essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, illustrating a variety of workers from the 19th to early 20th century.

“With starting the book with Solicitor, I really think of that as the founding story of my family,” said Kelley. “It’s the story my mother and grandparents told me pretty regularly.”

Trying different tactics, Manigault-Bryant picked excerpts from the book she liked and read them to Kelley for her reactions because “it wasn’t something she’d seen Kelley do in other interviews.” Manigault-Bryant also asked Kelley to read her own excerpts she found significant.

Picking her favorite excerpt to read aloud, Kelley chose the conclusion, a chapter dedicated to how she remembered her grandmother, Blundell, before she died.

Dr. Kelley reads excerpt in “Black Folk” about her grandmother. (Photographed by Jessica F. Simmons)

“I learned the depth of what she suffered not in her kitchen as a child, but in archival records as an adult,” she read from the chapter, after raising the book to the crowd, showing the audience the photo published in the book of her and her grandmother hugging and holding each other’s hand.

The event took place in the Hitchcock room of the Stone Center where Drammeh said the number of attendees surpassed what he planned for, reaching 130 attendees. The majority of attendees were students.

“I think that’s what helped me – some professors sending their classes over for students trying to get live credit,” said Drammeh.

Towards the end of the event at 7 p.m, Manigault-Bryant opened the floor for questions from the audience.

Lois Deloatch, Durham native and attendee, started the conversation. She asked Kelley to expand on just how long the journey took to research her own ancestry and write the book.

Kelley said that “finding her family trees” took 12 years of research and that she started the book in 2019 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finishing the event, the Stone Center hosted a reception to offer Black Folk for sale, an opportunity to get a copy of the book signed by Kelley, and provided food, catered by the Root Cellar Cafe & Catering.

Along with Black Folk, Bull’s Head Bookshop brought Kelley’s first book to the event, The Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson, for purchase.

It was the book Tim Smith, Creedmoor native and retired worker from Duke University waited in line for to purchase. He already owns a copy of Black Folk, and is a frequent attendee of the events on campus.

Smith said that he loved Black Folk, which appealed to him “because it was about the working class.” It reminded him of a book he read regarding Black women working in tobacco companies.

Prior to the event, Kelley said she hoped the audience would read the book and be reminded of “all the ways in which Black history and everyday Black experiences are American history” and they “are constitutive of the stuff that can tell us about our past and our present.”

“We don’t need to see Black history as a side story because it really is fundamentally America,” she said.