After Garnell Hill discovered he had a six-year-old son in 2020, the 41-year-old Burlington man decided he wanted to raise the child.

Since the boy had been taken away from his mother and had been in foster care since 2018, Hill was told by a social worker that it would be easy to unite with the boy he’d never met.

“This has to be a miracle,” Hill said the social worker told him over the phone.

The North Carolina Judicial Branch (NCJB) states that in its best practices and guidelines, 75 percent of reunification hearings in cases occur within 330 days and 100 percent of reunification hearings of cases occur within 510 days.

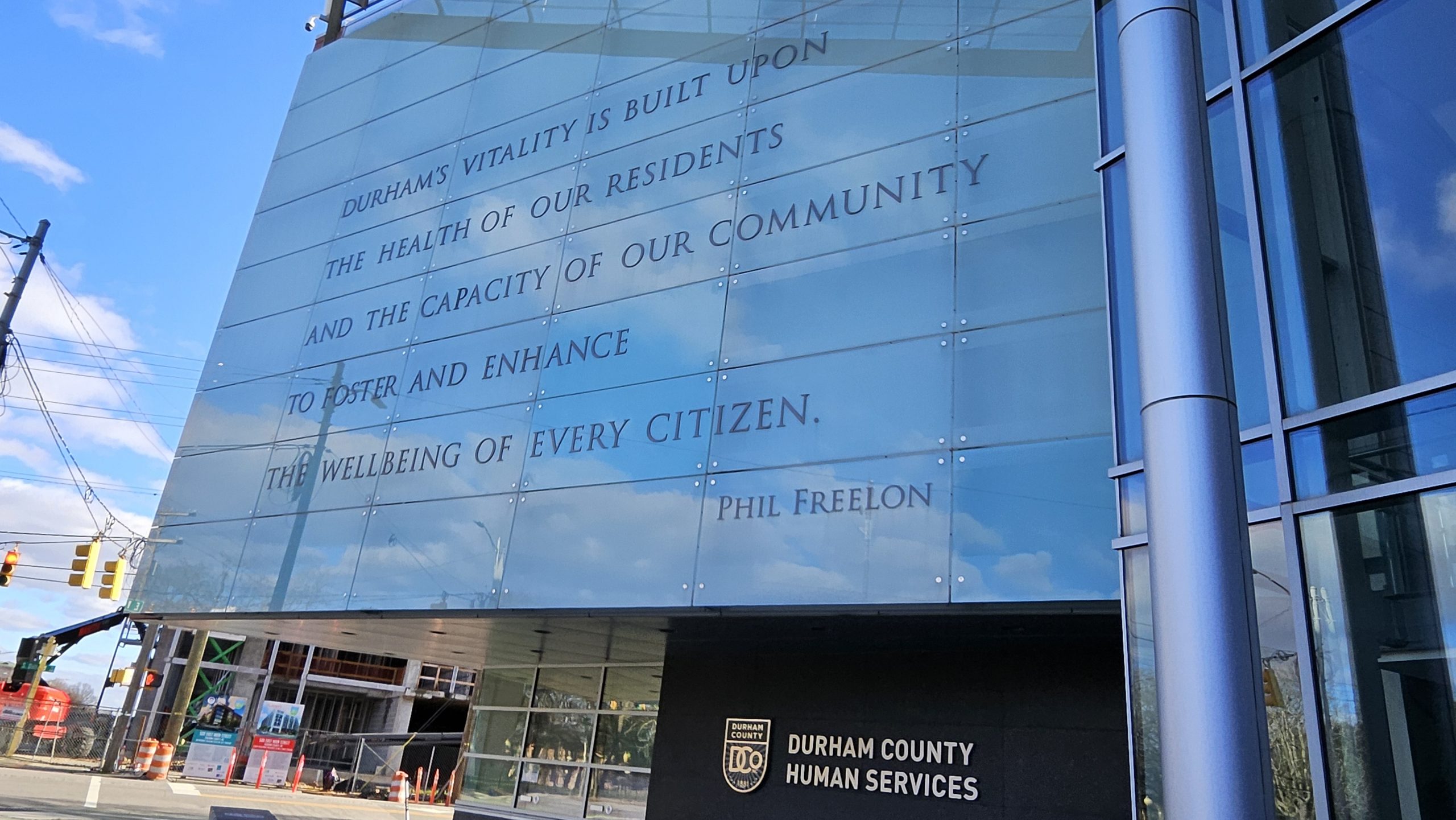

But three years later, Hill remains entangled in an ongoing legal battle with the Durham County Department of Social Services (DSS) to prevent the termination of his parental rights (TPR) and gain custody.

A judge can terminate a parent’s legal rights if there is grounds for doing so, and it is in the best interest of the child, according to the NCJB.

State records show that North Carolina courts have “terminated the rights of nearly 1,200 parents per year since 2018, with an average of 32 cases annually in Durham,” according to a November 29 article by WBTV and The Assembly, two news outlets from the region.

“They’d rather have him adopted,” Hill said. “I don’t know what the benefit is for them but it’s not fair to him or me.”

Amanda Wallace, former Durham DSS social worker and founder of Operation Stop CPS, an organization where the goal is to abolish child protective services and educate society about the wrong-doings of the system, said the saddest part of this particular case is the lack of interest for what the boy wants.

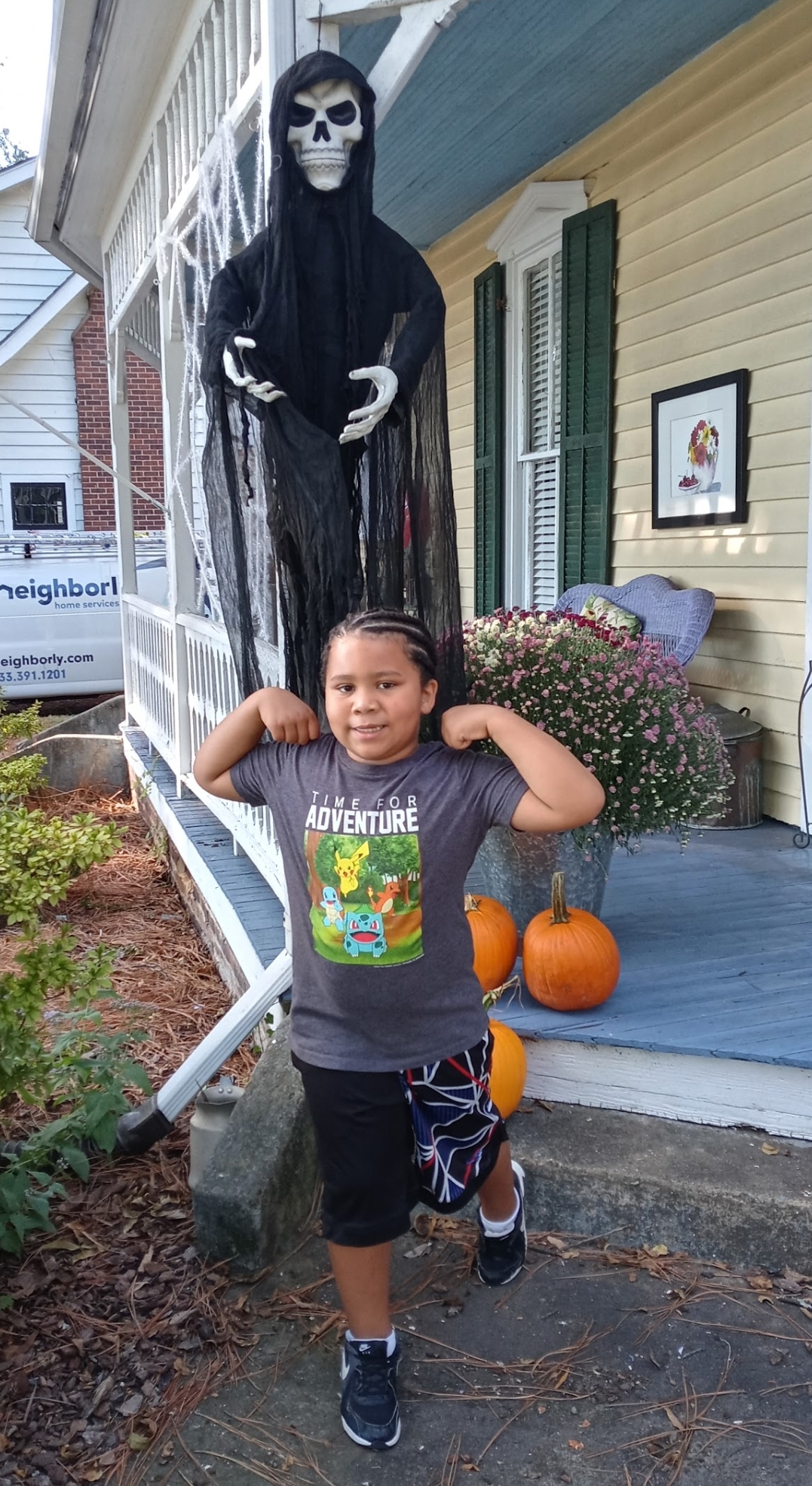

“He’s nine years old now, and he just wants to be with his father,” Wallace said. “And you see this child in videos, just saying ‘I don’t want to be in foster care. I’ve been here forever.’ Now he’s acting out and really having a hard time in his foster homes because he just wants to be with his father.”

Elizabeth Simpson, strategic director and attorney at Emancipate NC, said that North Carolina’s best interest of the child model is a “problematic frame.”

“The way I see it operating, it is disregarding a lot of literature about how traumatic it is to separate a child from their biological kin,” Simpson said. “That in and of itself, is trauma and an extreme harm [to the child]. It also does not take into account the express interest of the child.”

Emancipate NC is an organization committed to “dismantling structural racism and addressing mass incarceration throughout the state of North Carolina.”

Hill’s case “just doesn’t make good sense,” Simpson said.

“There are no allegations or proof that he ever did anything wrong whatsoever,” Simpson said. “It’s backwards that they’re still giving him a case plan and making him jump through all these hoops.”

Discovery of a son

Hill first learned about his biological son through an interaction between his cousin and the son’s biological mother. At the time, Hill was living in Washington, D.C., and working in a food catering business, while the biological mother was living in North Carolina.

“She said we had a six-year-old son, and he’d been taken [into foster care] since he was three years old,” Hill said.

Hill said that he had not been in contact with the child’s mother since 2014. Even though he knew she was pregnant, Hill said that the mother insisted that the child was not his.

Knowing nothing more about the boy or the situation, Hill contacted multiple social service departments in North Carolina to see if he could find his son. Durham’s DSS responded a few days later.

That is when Hill said he learned from a social worker that the mother’s rights were scheduled to be terminated in two weeks, so his son could be registered for adoption.

“She said ‘If you are the father we can get a continuance,’” Hill said.

To confirm his paternity, Hill took a test in October 2020, which resulted in a 99 percent match.

“It wasn’t even a second thought. I instantly fell in love once I got the results.” Hill said.

Because of the confirmation of his paternity, Hill was provided more information about the boy, including his name, Ian.

Hill moved to North Carolina and lived with his mother in Burlington temporarily to build a “face-to-face” relationship with Ian.

Hill said the social worker gave him the impression that once he showed DSS employment and stable living arrangements, he would gain custody of Ian within three months.

However, Hill didn’t meet the boy for nearly a year until May 2021.

Hill said he learned more about Ian through Ryan O’Donnell, Ian’s fourth foster parent at the time, who reached out to Hill through social media and the two built a relationship with Ian.

Hearing the way Hill spoke about his upbringing with his other three adult children, O’Donnell said it “spoke volumes.”

O’Donnell said the social worker assigned to the case at the time told him and his wife, Kelly, that the boy would go to his father once Hill proved paternity “because there was no reason for [Ian to be kept] from Garnell’s care.”

Visitation revoked

In November 2021, Hill was granted weekend visitations with Ian.

To lessen the burden of his mother housing two more people in her “tight apartment,” Hill said he moved out and rented a boarding room in Burlington to save money for a home in North Carolina for himself and Ian.

“We had Christmas there, and a couple of his birthdays too. It was a little spot, our spot, but the court got wind of it,” Hill said.

In July 2022, O’Donnell said DSS workers sent Hill a court order addressing housing. Hill said that they did not like where he was living.

“They said that I lied on my application, and I wasn’t staying where I said I was staying,” Hill said.

And because of the error on the application, Ian’s weekend visits were cut short.

To aid with Hill’s housing issue, O’Donnell bought a home and worked with Hill to set up a rental plan. After the approval of the court, Hill was then granted weekend visitation again.

“I’ve never been asked to do a random drug screen. No one asked me if I’m a fit parent,” O’Donnell said. “I did like 40 hours of classes, and I am licensed as a fit parent. Garnell has had more parenting education ordered by the court than I have.”

O’Donnell said he did not appreciate the way Hill had been treated by the court and DSS. The more work Hill put in to prove being a fit father, O’Donnell said the court and DSS always found “another thing to be upset about.”

He and his wife put in their notice to stop being foster parents immediately.

O’Donnell said by closing their home to foster care, the boy would have no choice but to go to Hill’s mother in Burlington.

But District Court Judge Doretta Walker of 14th Judicial District Court Walker said Hill’s mother’s house did not meet their housing standards due to a ditch in the backyard, according to Hill. Ian was moved out of the O’Donnell’s in November 2021 and placed into his fifth foster home.

Visitation revoked again

Even though Hill never faced any reports of substance abuse or neglect for Ian or his other three adult children, Hill completed parental courses administered by Walker to prove his fitness as a parent.

“I tried to bring it up [his other three children] at a point, but it blew right by like it never meant anything. I’ve been a father since I was 17 years old.” Hill said.

Over the course of several more court dates, he completed additional classes required by the court for his custody petition.

“I went through at least five or six different classes. But every time I go to court, they wanted me to do something more,” Hill said.

The situation escalated when Ian’s biological mother claimed Hill was using drugs. When he tested positive for marijuana in a drug screen, which is not legal in North Carolina, his visitation rights were revoked.

Keke Woods, a social worker and director of healing at Operation Stop CPS, said in most cases like Hill’s, parents are “guilty until you’re proven innocent.”

She said parents who test positive for THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol – a psychoactive compound found in cannabis, are “penalized, despite it having nothing to do to alter a person’s ability to be able to take care of their children.”

“They give you this impression that if you just do what they asked you to do and you’re cooperating – [there will be] no problems,” Woods said. “You agree to do something that you don’t actually have to do 99 percent of the time. That [drug test] is then used against you and then they will drug test you for everything.”

To regain visitation, Hill underwent multiple random drug screens. With inconsistent results during the first year but a consistent round of negative screens following, Hill was allowed weekend visitation with Ian.

But an incident occurred after Hill and Ian’s second Christmas together in March 2023 that limited Hill’s visitation to four hours a month – “two hours every other Sunday,” Hill said.

“I was bartending at this restaurant during the time which I no longer work at… [Hill and his co-workers] went out and celebrated a coworker’s birthday,” Hill said. “Stuff was getting put in people’s drinks all night that night and I drank one [unknowingly]. When I took that drug screening on that Monday, it came back that I was positive for cocaine.”

Hill said when he found out the result of the drug screen, his social worker “told me with great ease and enthusiasm. She was happy. She wanted me to slip up.”

To prove to the court he did not have a drug problem with cannabis and alcohol and follow their instruction of “staying clean” to gain custody, Hill admitted himself into a substance abuse program and stopped smoking marijuana for nearly a year, he said.

The fight continues

Hill said despite all that the court has made him do, DSS is now trying to terminate Hill’s parental rights of Ian.

The Durham VOICE reached out to DSS officials and was sent to voicemail several times.

“They say that now we had to get to continue because it went from reunification with dad and son, which was the primary plan,” Hill said. “To him being adopted and then terminating my rights as a parent…They want me to hurt myself and they gave me enough time to hurt myself the first time.”

A court date is scheduled for December 14 at 9 a.m. It will be day 1,978 since Hill has been trying to obtain custody.

Hill said every time he goes to court, he feels “criminalized” and “on trial for something I did wrong.” But he is “just praying for the best.”

Eric Williams, Hill’s lawyer, said he can not talk about his client’s case, but he is hoping for a “positive outcome” for the upcoming day.

Wallace said Operation Stop CPS and other supporters, such as Emancipate NC and Civil Rights Corps (CRC), plan to “pack the court” to provide support to Hill and court watch.

CRC is a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., and committed to confronting systemic injustice within the legal system of the United States.

The day before on December 13, CRC will partner with Operation Stop CPS to host an event on the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Law’s campus at 4 p.m. to prepare the community of the procedures to court watching in cases like Hill’s.

Erin Cloud, senior attorney at CRC, said court watching is “one of the most fundamental ways the community can hold courts to account.”

Learning of Hill’s case, she said is “very concerned about the way Mr. Garnell has been treated throughout this case.”

“[He is] a father who did assert his paternity, to come get his child out of a system,” Cloud said. “We should be minimizing barriers for that and not increasing barriers or even maintaining barriers.”

“The courts messed up a lot of stuff. They took a lot of time from us,” Hill said. “[Ian] knows where home is and who his dad is. Me and him just want him to be home.”

Gina Davis says:

Hi, my newborn was taken from me. This is going on all over the State of North Carolina. Please can you do an investigation on Department of Social Services-Guilford County?